Yes! No. Maybe?

No one knows, and it doesn’t matter to long-term, goal-focused, and planning-driven investors. Always remember, the market cannot be timed.

By definition, no one knows for sure that we’re in a recession while we’re in the recession. A recession is 2 consecutive quarters of GDP decline, and they’re “called” by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) – usually some months after the data comes in suggesting that we did in fact have a Recession.

By the time the recession is called, the recovery is under way. Many times, markets have already bottomed and started their “V” recovery when the NBER confirms that we just went through a recession. We can’t know if we are in a recession. Even if we could know we were in a recession, we couldn’t know how long it might last or what might trigger the recovery. This makes the recession prediction pretty useless in terms of setting investment policy.

Still, the public frets a great deal when the pundits start to forecast the onset of recession.

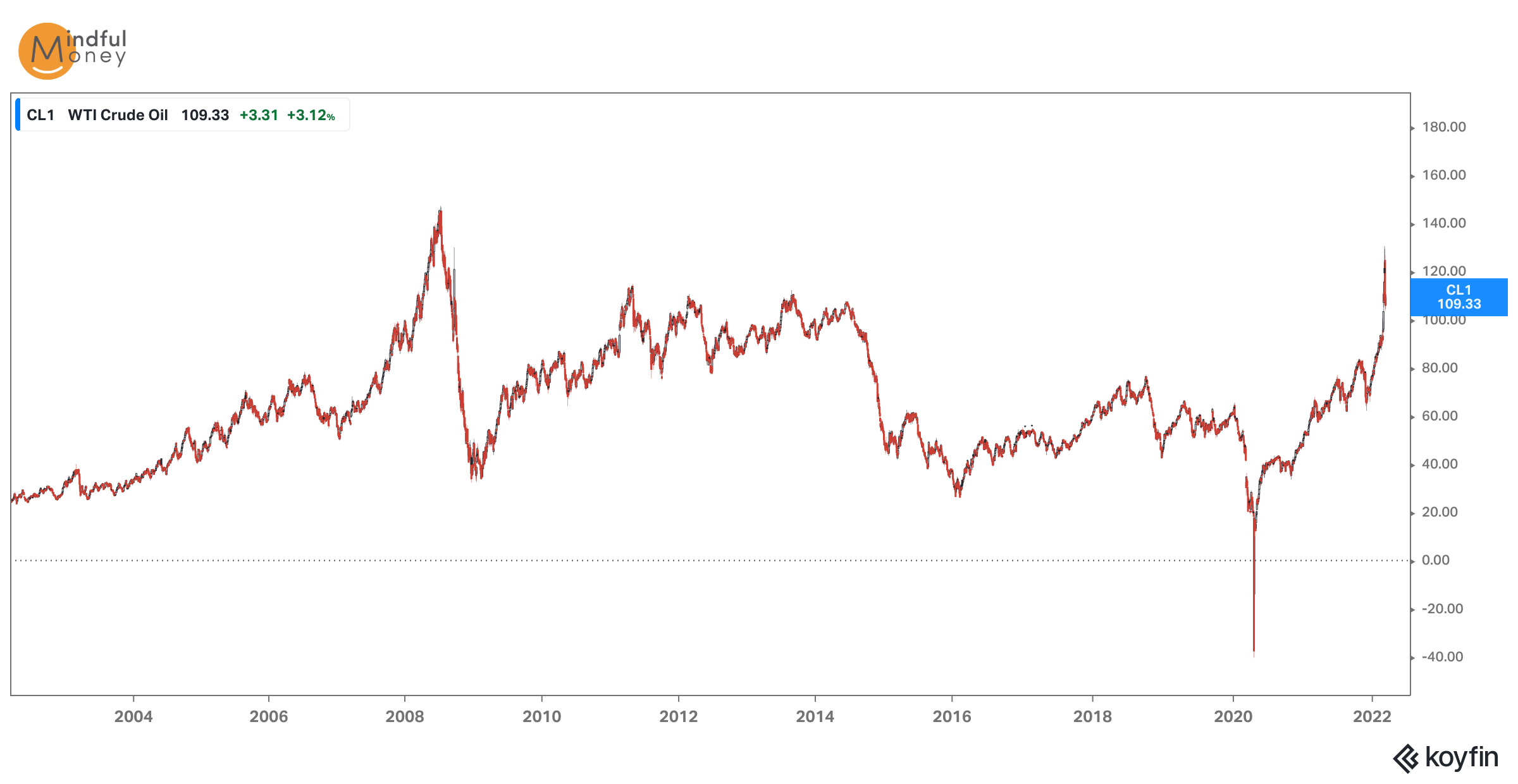

And… here we are. Two of the most popular indicators of pending recessions are spikes in the price of oil, and the inversion of the yield curve. If we went by these two items, we’d have to say that a recession may be coming.

Oil prices were already increasing before Russia invaded Ukraine. Looking over at the right side of that chart, you can see that the price of crude oil spiked up last week as Biden stopped the US import of Russian oil.  This was the lesser of two evils. He decided that further isolating Putin was worth the risk of higher energy prices (in an already inflationary environment). It was a hard choice, but a good one.

This was the lesser of two evils. He decided that further isolating Putin was worth the risk of higher energy prices (in an already inflationary environment). It was a hard choice, but a good one.

So, with 3% of US imports not available for some period of time, the analysts are falling all over themselves to pinpoint the peak price for a barrel of oil this cycle. And they have only begun to sound the recession watch alarm. I’ve seen one suggest we are on the way to $300/barrel. And, while that would certainly cramp everything in the economy, it isn’t a high-probability outcome.

Just last year (as energy prices dropped to their lowest points in history), there was a conversation about pricing for barrels of oil in the $60s. The problem was that the low price renders many wells in the US unprofitable (meaning it costs $60 to bring those barrels to market). Oil below $60 means those wells cease to flow.

The flip side of that argument is oil at $100 must be wildly profitable for those wells AND for other – more expensive – wells at the same time. Every dollar above $100 increases the incentive to produce more.

That’s how commodities work. If the price of a commodity rises, more supply becomes available. As more supply becomes available, prices moderate. If too much supply comes available, then prices fall again. As prices fall, the more expensive production sources reduce production and the cycle repeats.

Yes, this can be an inflationary kicker (and we certainly don’t need that), but it is inevitably short-lived and impossible to time. We shouldn’t change investment policy due to a spike in oil prices.

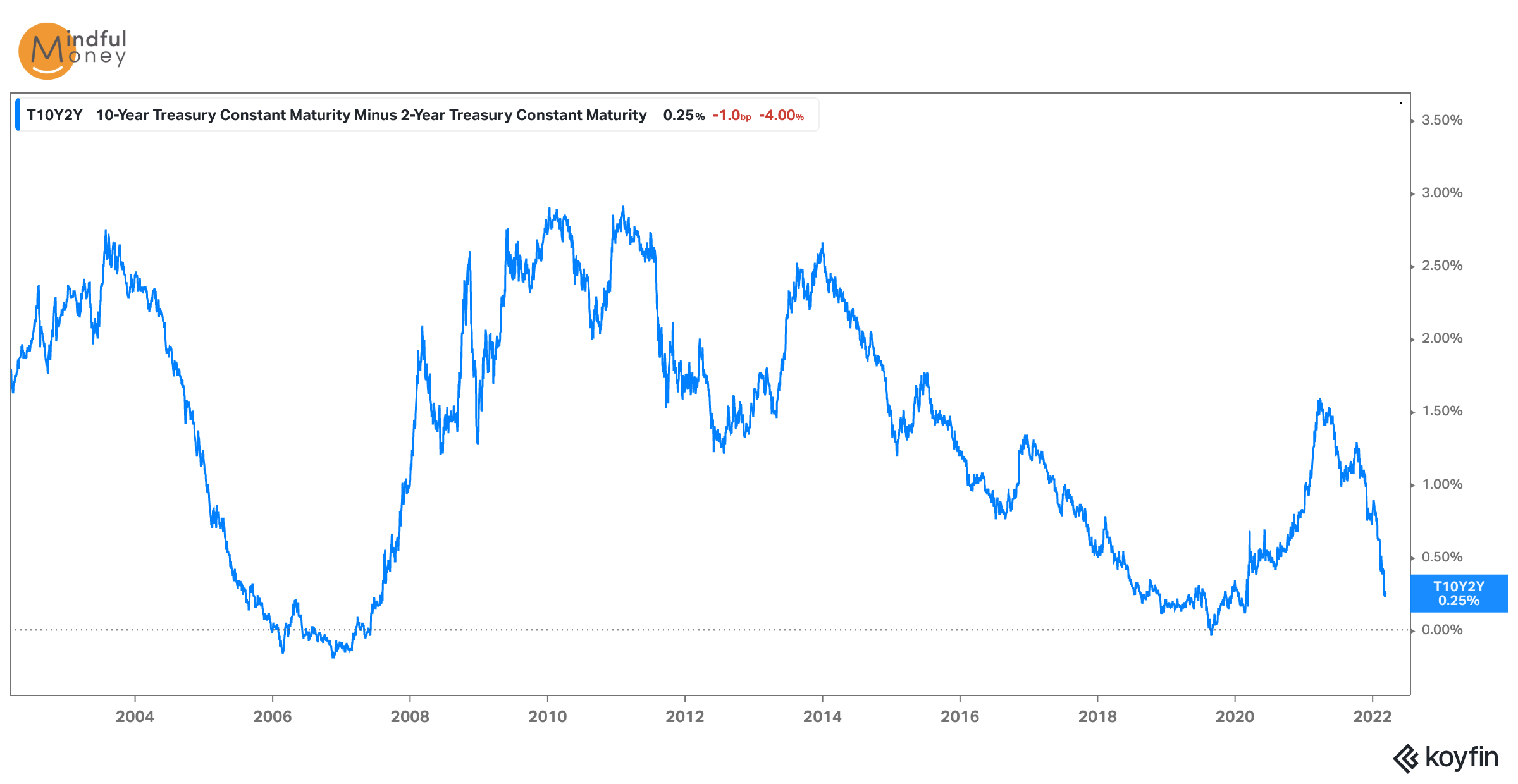

At the same time, we are getting closer to a yield curve inversion (where the 2-year Treasury rate becomes higher than the 10-year Treasury rate). The popular wisdom is that when the blue line in the chart below crosses zero, we are within 12 months of the start of a recession. While the expected pace of rate increases has moderated since Russia invaded Ukraine, the FED has clearly indicated that they will still be raising rates multiple times this year starting with the March meeting. The question very quickly becomes, if they raise rates 25 basis points (bps) or .25%, will that increase rates of the 2-year Treasury enough to make them higher than the 10-year Treasury? What if the first hike is 50 bps or .5%?

While the expected pace of rate increases has moderated since Russia invaded Ukraine, the FED has clearly indicated that they will still be raising rates multiple times this year starting with the March meeting. The question very quickly becomes, if they raise rates 25 basis points (bps) or .25%, will that increase rates of the 2-year Treasury enough to make them higher than the 10-year Treasury? What if the first hike is 50 bps or .5%?

Clearly we are on the edge, and it is a distinct possibility that we will see an inverted yield curve in the next 6 months.

The price of oil is spiking (a harbinger of recession) and the yield curve, while approaching inversion, may get a shove from the FED in the coming months. If the curve inverts, this starts the clock ticking for recession within 12 months (an accurate predictor, if not a very accurate timing mechanism).

These are 2 very clear indicators of the potential for recession and – fair warning – in the coming weeks, it is likely that this will take over the media conversation. Some combination of war, oil price spike, and inverted yield curve will come to be seen as natural predictors of recession. The what’s-working-now-crowd will be pushing the sale of equities as the best strategy.

Given current and potential headlines… what should we (goal-focused and planning-driven investors) be doing in our portfolios?

Or, as an investor may ask the question… If there is going to be a recession, shouldn’t we get out of the market or reduce our equity exposure until things settle down?

NO. The market cannot be timed.

Getting out (for any reason) is only the first half of a two-step process. Reducing equity exposure begs the question, “When will we add the equities back into the portfolio?” Don’t say “When things settle down,” because this is likely to be too late – well after markets have already begun their V recovery. Historically, getting out and waiting-to-see-what-happens results in lower returns (and higher taxes) than does just riding out the current economic issues.

Again, the market cannot be timed.

The only sure way we have to capture the full long-term return promised by our equity holdings is to be willing to participate in their unpredictable, irregular, temporary declines.

The impulse to get out of equities in anticipation of some market or economic issue is fundamental to human nature. You will always feel the impulse. The trick… is to let the impulse go BEFORE you take any action in your portfolio.

There are a few simple practices you can engage to help you stay the course when it doesn’t feel good to do so.

First: Stop doom scrolling. We have more media at our fingertips than ever, and when things are bad, the worst thing you can do is read how bad they are over and over and over again on every media source you regularly attend to. Plug your phone in, down in the crawl-space, and grab a book or go for a walk. Or, do what I do –

start watching comedians. I happen to love Michael Che and Josh Sneed. Check out drybarcomedy.com for relatively clean comic variety.

Second: Recognize, and accept the anxiety that comes from not knowing what the outcome of today’s events might be. Don’t judge your worry, accept it as a natural human response to seeing others suffer. At the same time, know that your brain has an action bias. It really, really wants you to do something, anything… even when doing nothing is the better choice.

Third: Remember that uncertainty is the norm. Today we’re worried about inflation and high oil-prices. One year ago it was lack of inflation and low oil prices (remember oil falling below $0). Volatility is not a bug, it’s a feature of a market economy. More uncertainty leads to more volatility. Neither more nor less volatility yields an improvement of predictability. The market CANNOT be timed.

Fourth: Always keep in mind that as quickly as a thing started, it can end. If there is major economic disruption, there are motivated actors trying to figure out how to reduce the disruption. In some cases, they are governments trying to provide supports. In other cases, there are businesses responding to the profit motive. Price and value are always and everywhere inversely correlated. As price declines (all else being equal), value is increasing. The further down a market goes, the faster the rebound can be. Have patience. Do I need to say it again? The market cannot be timed.

Fifth (and final): Remember our mantra: “This too shall pass.” Every single time there has been a headline that suggested the downfall of the generalized market economy, it has been wrong. Every. Single. Time. The media wants you to believe that “This time is different,” but it never is, in one very important aspect. As different as it presents itself in detail, the phrase “This too shall pass” will ultimately apply.