Last week, we introduced the constant competition between two camps of investors: the Active vs. the Passive. And, without taking a stance re: financial outcomes (performance is entirely unpredictable), we made the case that a passive approach might be the better approach. It is the one I choose personally, and recommend often – if for no other reason than its requiring so much less of our time and energy (“opportunity costs,” if you will).

“But, Jonathan, I really want to outperform.”

I get it. So do I. And… future relative performance is entirely unpredictable and uncontrollable. No one can get in at the bottom and get out at the top on a predictably consistent basis.

If you choose to be more active yourself or you hire active management, you are setting up not one, but two hurdles that your (or the manager’s) investment acumen must overcome. First, you are probably adding cost in the form of transaction costs, bid-ask spreads, or actual manager costs. And second, your transaction (if successful) will create regular, realized capital gains which will generate taxes owed.

Today, I want to set all the opportunity cost and real cost issues aside, and ask the question of whether an active approach outperforms.

There are two answers. The first is that every year, people who over-weight the best-performing securities DO, in fact, outperform.

You can access JP Morgan’s Guide to the Markets HERE.

According to the above, picking a random year, in 2013 anyone who over-weighted small-caps did far better than those who decided to bet on emerging markets. In fact, pick your year, and you can see which asset classes did well that year and which asset classes did poorly. If you over-weight the top of the chart, you do well; if you over-weight the bottom, you do less well. No one knows which asset class will be on top next year.

Or, more specifically, if a manager of large domestic (U.S.) companies had over-weighted the following outperforming stocks in 2021, they would likely have outperformed other managers and their index (depending on what else they may be over-weighting). A manager who wisely (read: luckily) picked these exact 10 companies, and only these companies would have “Crushed It” with a roughly 135% showing for the year. Wow.

- Moderna Inc. (MRNA): +170%

- Devon Energy Corp. (DVN): +155%

- Ford Motor Co. (F): +132%

- Bath & Body Works Inc. (BBWI): +131%

- Marathon Oil Corp. (MRO): +130%

- Diamondback Energy Inc. (FANG): +118%

- Nvidia Corp. (NVDA): +117%

- Fortinet Inc. (FTNT): +117%

- Nucor Corp. (NUE): +114%

- Gartner Inc. (IT): +104%

This is from a US News Article: HERE.

Yes. Outperformance does happen. It happens every year.

When a manager outperforms, their companies push them out into the press. The marketing departments take over, the headlines get created, the “relative to benchmark” graphs get produced, new explanatory whitepapers get printed, the press kits get refreshed, and the interview circuits begin. The outperformers are touted as experts at the top of their game.

Please note: This is NOT done to offer praise for a job well done. This is done to attract new assets (and increase fees collected on management).

But what happens the following year? Do top managers stay top managers?

No.

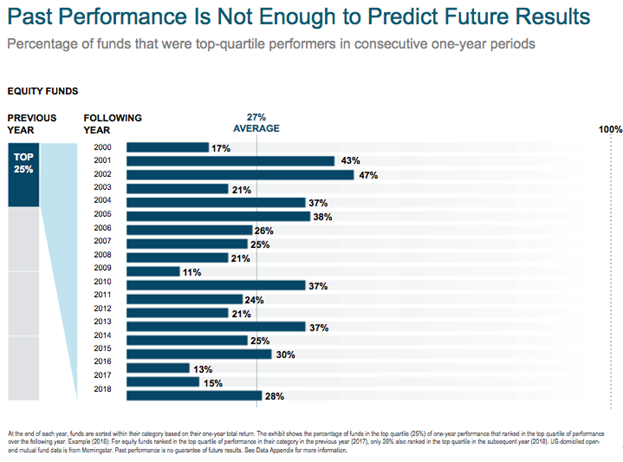

This is From a Dimensional Funds presentation entitled: Extended Persistence.

I apologize for the age of this slide… but the story hasn’t changed. Top managers do not stay top managers from year to year. For a more recent example, consider Cathie Wood’s ARK Investment Management – a number one performer in 2020, posting some of the best annual returns anyone had ever seen –

followed immediately by an enormous crash in 2021, as the very same sky-rocketing holdings that paid off so well the year prior came back to earth.

Still, active management continues to draw investors, and day traders still exist. Why?

Hope springs eternal.

We don’t know (can’t know) the future. This year, it could be different. No one can tell. Your experience could be different than the average. You may be smarter. That is, of course, the hope – that you will be the one who picks the stocks or the manager who cracks the code – and does better consistently.

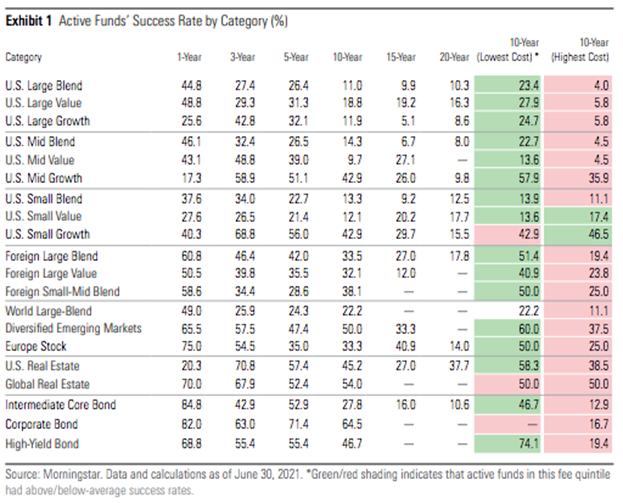

Is it worth trying? I think every investor has to decide for themselves. But, just before you decide, let’s look at the probability of outperformance over time. Here we see Morningstar’s analysis of Active portfolios vs. Passive portfolios. The numbers in the graph represents the success percentage of the active funds in the category (on the left) for the time period (across the top). Notice how, down the 1-year column, the success percentages are all in the middle- to high-range (with the most success being found internationally and in fixed-income), but by the 15th and 20th year, the success percentage has dropped to the single-digit or low double-digit range (everywhere except Real Estate).

You can sign up to receive the full study HERE.

You may or may not “outperform” in the short run… we can’t predict. On average, in the US, less than half of managers outperform over one year. Internationally and in fixed income, the averages for outperformance are higher over a single year (this may even be tempting you as you read).

There are some managers every year who do outperform, but there is no way to consistently predict which managers they will be from year to year. And…

The longer you hold an active manager regardless of geography or asset class, the lower the probability that you will be holding an outperforming manager.

Now. If you are reading a blog named Mindful Money, then some part of you already knows that money does not belong at the center of our lives. If you haven’t read it, we talked more about this last week, HERE. My hope is that today, you can take away the idea that putting money in its place (spending fewer resources on it, and suffering less anxiety about it) says NOTHING about the investment outcomes we might experience.

Spending more time and effort and anxiety actively managing our portfolios does not equate to better performance. In fact, looking at all the above, the opposite might actually be true. Short-term investment outcomes are just as much a function of luck as they are a function of skill – perhaps more.

So, am I saying that portfolio design doesn’t matter? No. There are proper ways to construct and manage a portfolio which give you the opportunity to ignore the short-term gyrations, and achieve better long-term outcomes. They just have very little to do with the investment-selection and market-timing that is so often discussed in popular press.

We’ll talk about those ways next week.